When it

comes to informing the public about a toxic exposure like lead in drinking

water, just about every kind of misstep can occur. Officials disguising facts or

offering up alt facts, faulty water contamination tests, dueling experts and

scientific uncertainty and plain and simple incompetence. Maybe there was a time in

the US when we walked around not worrying about how safe our drinking water was,

but that was pre - Flint MI (2015) and now, pre Newark NJ.

Last night with the NJ governor and Newark mayor front and center

at a media event NJ announced that the

city of Newark will receive

a $120 million loan to get poisonous levels of lead out of its drinking

water, and they’d do it in less than 3 years. Once again, from the public

outrage play book, it wasn’t until scared, angry residents + national bad press

combined to get sensible, necessary action.

I’m not qualified and

don’t have the stomach for delving into the underlying mismanagement and incompetence

that inevitably goes into many public health emergency like this one. I

won’t mention that lead levels in Newark’s drinking water are so high that the

New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection issued notices of non-compliance to the city in both June 2017

and January 2018. And I won’t enumerate the ill-conceived, too little – too late, tortured

steps the city took that backfired – home water filters that didn’t work, and a

Lead Service Line Replacement Program that would have taken 8+ years and would cost

each home owner $$. The NYT is doing an excellent deep dive on this.

Instead I will talk about one kind of problem I’ve made my home

for over 40 years - how to communicate often complex health and science to general

publics. The case studies about what works and what doesn’t are legion. In recent history there are Katrina, H1N1,

Ebola, pesticides in food, arsenic in rice, and lead and other toxicants in

drinking water. If pressed to get to the point I’d say there are 3 or 4 things

that perennially go very wrong when official notices about an environmental

hazard are written. That’s what I’ll be talking about. And when I write about

these things, by necessity, I seem to wind up revealing how officials – often popular,

likable, trusted individuals, mysteriously lose all powers to communicate

clearly. Why? And what’s the fix.

Clear Language

The importance of clear communication to inform and help the

public stay safe and healthy is not new. There are many long-standing efforts

by the Federal Gov’t to promote clear communication. The Plain Writing Act (

2010) requires federal agencies to write “clear government communication that

the public can understand and use.”

Federal agencies publish and promote how important it is to use

clear communication. There’s a whole federal website on how to write

plainly so that the largest numbers of people can understand information.

Other federal sites : CDC Clear Communication – Everyday Words For Public Health Communication.

https://www.plainlanguage.gov Plain

language sites even has sample templates writers and designers can use to create

readable, understandable health information.

Newark's Got a Communication Problem

When I looked over Newark’s water quality reports (2017 and 2018),

both with personal introductions from Mayor Baraka, I encountered convoluted

sentences that had little meaning, terms only a scientist or toxicologist would

understand and charts with mind-numbing ppm (parts per million) numbers for

lead levels. I did a health literacy load analysis on the Mayor’s 2018 brochure.

The analysis is simply a process of “unpacking” the writing to identify words,

sentences, & graphics that are “high barrier” – things that will likely

make it hard for readers to understand and use the information (Zarcadoolas,

2006, 2008).

I didn’t have to look far.

3 Things You Don’t Want to Do if You Want to

Communicate Risk Clearly

In both the 2017 and 2018 brochures Mayor Baraka proclaims, (my

highlighting)

“I am pleased to present the Water Quality Report,

which confirms that the City of Newark’s water is

not only safe to use and drink but that it is some of

the best water in the State of New Jersey.

Many of you have heard or read the outrageously

false statements about our water but please know

that the quality of our water meets all federal and

state standards. The only high lead readings were

taken inside of older (pre-1986) one-and-two-family homes that

have

lead pipes leading from the City’s pure water in these structures.”

I’ll leave the assault on truth aside and focus on the 3 communication elements that hobble

the report in terms of its usefulness to the public.

1 Difficult

Words There is basically only one sentence in the report that says there

is a lead problem. But the problem is a very disguised because it uses a very

difficult word. If you don’t know what that word means you lose the

meaning. (again my highlighting)

LEAD:

In the first half of 2017, and the second half of 2018, the City

of Newark experienced a lead exceedance

in its drinking water. Elevated lead levels were particularly found in samples

taken from homes with lead service lines.

“lead exceedance level”

Not the easiest way to say what you really mean –

How about

The amount of lead in the drinking water exceeds (is greater than)

what the Federal Gov’t (EPA) says is safe. We found high levels of lead in water

samples that came from homes that have lead pipe lines.

Also, from a science/civic literacy perspective, if you don’t know

that the federal gov’t sets safe levels of many chemicals, the reference to

levels loses its import.

2 Hard to Read

Sentences

Overly long and complex sentences are another typical problem in

health communications.

a. Where did the

verb go?

A common thing you see in technical or official writing is a

sentence like the following:

In explaining what the city is doing to address the lead level

problem:

“These efforts include: (my underlining)

• Distribution of free filters

and replacement cartridges to qualified Newark residents.

· Implementation of the Lead

Service Line Replacement Program, which will assist property owners with the

replacement of their lead service lines at a reduced cost.

These are what we call “nominalized” verbs – essentially verbs

trying to act like nouns.

Problem is we use the verb to pivot and help us keep who did what

straight in our mind.

Readers have a much easier time reading active sentences, like:

We are distributing free filters…

We are implementing (starting) a Lead Service Line Replacement

Program….

b. Overly complex

sentences

(This from the

Glossary at the end of the Report)

Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG): The level of a

contaminant in drinking water below which there is no known or expected risk to

health. MCLGs allow for a margin of safety.

Let’s just say that “below which” and “above which” a hard

comparative/relative clause that many readers struggle with.

*Oh, and while we’re at it, generally readers don’t like

glossaries. This is because, unless it’s a hyperlink, they lose

their place going to the glossary and then going back to the text.

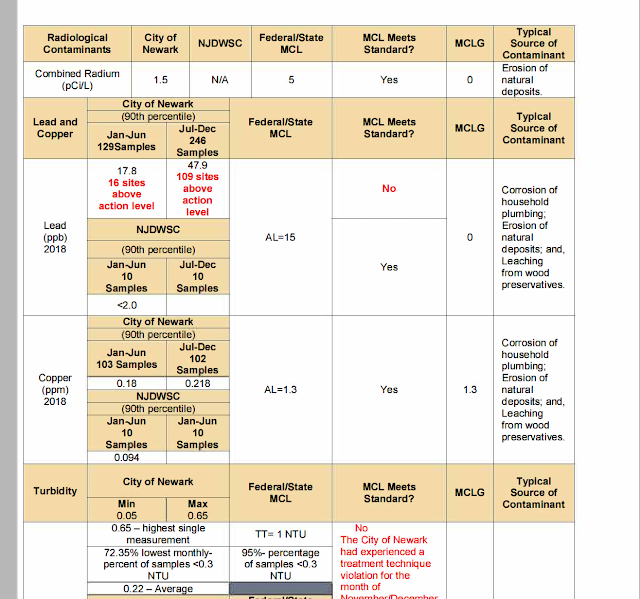

3. Numbers and Charts

Why am I always surprised!?

But this type of obfuscated – “Go ahead - just try to understand this chart”- really sets me off.

Why? Because there’s over 30 years of evidence showing that a

significant portion of the US adult population (90 million or more) has

difficulty understanding and using health & science (Rudd, 2002; IOM, 2004;

Zarcadoolas, Pleasant & Greer, 2006). And our ability to work

with numbers (numeracy) is even less impressive (Ancker as an example, as well as Zarcadoolas and Vaughon (2014).

The significant number of charts in the Newark Report use terms

and numbers that have very little meaning to millions of people. Plus the

preface to the charts uses difficult vocabulary, science concepts and complex

sentences. Trifecta!

Bottom line is there are endless reasons for failed public health

& safety communication. Elected officials minimizing and passing the buck,

besieged public works administrators, lack of funds to fix the problem, poor

advice from crisis managers and PR firms, scientists in charge of communicating

to the public, institutional racism and indifference. But far too often

those with the greatest health and social burdens have limited access to

understandable and actionable information. This happened in Newark. It’s shameful. It’s fixable.

I'll let Mayor Baraka close. Quite a commitment to clear communication!

Some references

Zarcadoolas,

C., Pleasant, A. & Greer, D.S. (2006).

Advancing Health Literacy: A frameworkunderstanding

and action. San

Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Zarcadoolas, C. and Vaughon, W. (2014). If numbers

could speak: low numeracy skills and the digital revolution. In H. Hamilton and

Chou, W- Y. (eds.), Routledge Handbook of Applied Linguistics and

Health Communication, New York, NY, Routledge.

Ancker JS, Kaufman D. Rethinking health numeracy: a multidisciplinary literature review. Journal Of The American Medical Informatics Association: JAMIA. 2007;14(6):713-721.

No comments:

Post a Comment