This Blog Was Written by

JEM

At the beginning of the #metoo movement, I noticed a number of things that brought me discomfort. First, as is common with American Feminism, women of color were often absent from the conversation. In fact, the fact that “me too” was an idea created and promoted a decade ago by Tarana Burke, a woman of color, and founder of JustBe Inc. The second was a deeper discomfort. One that I had felt before, but one that was threefold. First: I didn’t know how to be a part of this conversation. As a self-declared ally (I still don’t know whether I, or any man can ever truly be a feminist) I wanted to spread the word, again, that this was the experience of women. To remind people that too many (more than 1 in my book) women experience assault, abuse, misogyny, sexual aggression, and fear EVERYDAY. As a victim of sexual assault, however, I also wanted to share my own #metoo. I remember clicking through a few of my friends’ pages, men and women, feminists and victims, to see if anyone had “cleared” men to post about their own experiences yet, or if the subject had been broached. One male friend did, and another female friend told him it was OK. My worry was that I would, despite my best intentions, distract from a conversation about women who were victims of abuse at the hands of men, that this would seem more like a “#mentoo” than a simple show of commonality, solidarity, or shared opposition. I’ve felt this all too often as a male who has experienced sexual assault and who desires to be an ally.

That brings me to my second point of discomfort. Discussions about abuse and gender relations so often take the form of ‘Us v. Them’ where all women are on one side, and all men are on the other. I have been told that my voice is unwelcome simply because I am a man, without regard for my position on the matters being discussed, or the fact that I want to help. I understand that people need safe spaces, and I have always made my best efforts to steer clear of those safe spaces if I am not explicitly invited. I resent being painted as the enemy based on the gender I was assigned in the genetic lottery. There are so many men who wish for things to be different; some of us wish to be a part of the conversation, not just sign holders. We have ideas on bridging the gap, speaking directly to men, and even getting more men to the table, or standing next to women. That becomes difficult when men are taught that they are bad, and are put on the defensive.

JEM

How the everyday words we use

contribute to an unfortunate, everyday problem.

“Rape

is not a moment, but a language.” – Prof. Pumla Dineo Gqola, author and

activist

At the beginning of the #metoo movement, I noticed a number of things that brought me discomfort. First, as is common with American Feminism, women of color were often absent from the conversation. In fact, the fact that “me too” was an idea created and promoted a decade ago by Tarana Burke, a woman of color, and founder of JustBe Inc. The second was a deeper discomfort. One that I had felt before, but one that was threefold. First: I didn’t know how to be a part of this conversation. As a self-declared ally (I still don’t know whether I, or any man can ever truly be a feminist) I wanted to spread the word, again, that this was the experience of women. To remind people that too many (more than 1 in my book) women experience assault, abuse, misogyny, sexual aggression, and fear EVERYDAY. As a victim of sexual assault, however, I also wanted to share my own #metoo. I remember clicking through a few of my friends’ pages, men and women, feminists and victims, to see if anyone had “cleared” men to post about their own experiences yet, or if the subject had been broached. One male friend did, and another female friend told him it was OK. My worry was that I would, despite my best intentions, distract from a conversation about women who were victims of abuse at the hands of men, that this would seem more like a “#mentoo” than a simple show of commonality, solidarity, or shared opposition. I’ve felt this all too often as a male who has experienced sexual assault and who desires to be an ally.

That brings me to my second point of discomfort. Discussions about abuse and gender relations so often take the form of ‘Us v. Them’ where all women are on one side, and all men are on the other. I have been told that my voice is unwelcome simply because I am a man, without regard for my position on the matters being discussed, or the fact that I want to help. I understand that people need safe spaces, and I have always made my best efforts to steer clear of those safe spaces if I am not explicitly invited. I resent being painted as the enemy based on the gender I was assigned in the genetic lottery. There are so many men who wish for things to be different; some of us wish to be a part of the conversation, not just sign holders. We have ideas on bridging the gap, speaking directly to men, and even getting more men to the table, or standing next to women. That becomes difficult when men are taught that they are bad, and are put on the defensive.

“Men

should be offended when someone claims that women should prevent rape by not

wearing certain things, or not going to certain places, or not acting a certain

way. That line of thinking presumes that you are incapable of control. That you

are so base and uncivilized that it takes extraordinary effort for you to walk

down the street without raping someone. That you require a certain dress code

be maintained, that certain behaviors be employed so that maybe today, just

maybe, you won’t rape someone. It presumes your natural state is rapist.” –

Unknown

The third point of

discomfort is related to the second, but is more complicated. It is a question

that runs deep for me. How long have I been silenced? As a boy, I remember

learning gender roles. Boys wear blue, girls wear pink, girls do home

economics, boys do shop class, girls spend time on their looks, boys wear

whatever, girls talk about their feelings, and cry, boys “man up”. Most of

these didn’t stick with me as I got older. I wear pink, and basically whatever

else I feel like unless my wife tells me she’s not leaving the house with me if

I wear that. I can build and fix, but I can also cook, sew, and braid hair. I

was also amongst the first generation of “metrosexuals” (note the connotations

of that word too). A few things DID

stick with me though; things that I think stick with many boys as they get

older. 1. Boys don’t cry. This one stuck with me so much that after my

grandfather passed away in my arms when I was just 11 years old, I refused to

shed a tear. The women all wailed, while the men hid away to avoid showing

emotion. I was stoic, and proud of it. I called family members to tell them, I

called the ambulance, I covered my grandfather, I slept in his room that night.

I had taken the words of my father to heart. “You are a man of the house now”

he said, and men don’t cry.

I learned early on

that boys don’t talk about feelings, so it would be years before I faced my

emotions and realized what bottling them up meant, the additional pain it

caused me. I was bullied for being a geek, abused by a babysitter as a child,

lost after my grandfather, my most influential and stable male figure, passed

away. Then I moved to a new country at 13 to be reunited with my mother who I

had been separated from for 5 years. I was a mess, and I wasn’t supposed to talk

about it. I must say, these weren’t lessons actively taught to me. My mother

encouraged me to speak to her, but she wasn’t a boy. She didn’t get it. America

was worse than Jamaica. Being new was hard enough, but I wasn’t in any of the

cliques. I was a choirboy and a soprano, I liked purple, and I played tennis. I

joined the color guard because a girl I liked convinced me to, and then I was

definitely “gay”. I quit two weeks later because I couldn’t stand it. I joined

the football team instead. In high school, machismo ruled. I became angry and

aggressive, but also really good at hiding my emotions from teachers and my

mother. Eventually they all noticed, and I joined martial arts to channel my

anger.

All this time, I

never learned to express myself fully. I remember when I finally learned that

anger was just an explosion of other emotions. It came after a therapist tried

to get me to identify a range of emotions by name and facial expression. They

all seemed like anger to me. For the first time, at 25 years old, I was

learning to use emotional vocabulary. It was like learning a new language. I

had to learn to think differently, process my situations, and break down the

things I was feeling piece by piece. The process made me angry! As Colin Beavan put it “the fact that we are taught to

suppress so much leads to expressing only that which overpowers us—like fear,

anger, and aggression.” This was my case for many years. This is the case for

many boys, who then become men, who are faced with being the enemy, and unable

to express how they feel. This is compounded by adult male fraternity, alcohol,

and adulting. THIS IS NOT AN EXCUSE! I say this to point out that, like many

other things in our society that lead to pain, strife, and division, there is a

fundamental, systematic flaw. The way we raise our men is broken, and making

ALL men the enemy only pushes the broken, confused men further into the abyss,

and the ones who have managed to climb away from the edge, closer back to it.

"While female sexual empowerment

is an important factor in the struggle to end rape, it will not succeed without

corresponding shifts in how boys are taught to experience sexuality and

gender.” – Brad Perry, Yes Means Yes! Visions of

Female Sexual Power & a World Without Rape

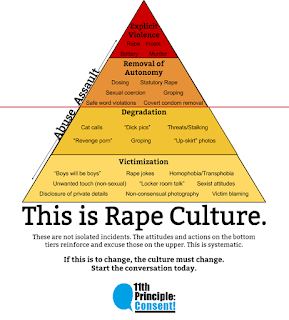

It all starts with

the language we use; “boys will be boys”, “man up”, “boys don’t cry”, “locker

room talk”, “sissy”; these words all enforce a problematic male culture and

stereotype. This language is all part of what Jackson Katz calls the “Tough

Guise”. To be male is to

be tough, rash, aggressive, unfeeling, dominating… bad. Some men try to live up

to these stereotypes, other men become victims of them, others still spend

their lives trying to shake them. Other language like; “girls play hard to

get”, “tipsy”, “smack that a**”, “beat the p***y up”, “c*ck block”, “c*ck

tease”, even language we use in seemingly innocuous conversation like “hit me

up”, or “shoot me an email”, serve to normalize violence both in our everyday

lives and our sexual experiences. It has become customary for us to use violent

language. We have literally internalized and assimilated violence into our

speech. In turn, society has become desensitized to violence. How can we expect

to teach people that violence is bad when we speak violence?

One of the most interesting things that I noticed after the emergence of the #metoo hashtag was that men started using #metoo or other hashtags like #HowIWillChange, #ihave, and #IDidThat, to admit to improprieties, and to pledge to change. While some decry this as distraction, men covering their asses, or men “performative wokeness”, I did see one interesting post from a female friend. In it, she described being in a relationship with a young man who, seemingly due to depression, lost his desire to engage in sexual intercourse with her. Upon bringing her dilemma to her friends, she was repeatedly told things like “Look at you! You’re gorgeous! What guy WOULDN’T want to have sex with you? Something is wrong with him.” Emboldened by these statements, she eventually guilted, and coerced him into sex. She used the #ihave to highlight how sometimes we do things that we don’t realize are sexual assault, or consent violations. This resonated strongly with me. How easy is it for a few simple words to change the way we perceive and act? How much would change if we stopped using language that enforced the “tough guise”, the male-female enmity, and rape culture? I a member of what is know as the “burner community”. We attend events and form a community united by the 10 Principles of Burning Man. In recent years, consent has become a large ongoing conversation and is being considered an unofficial, but equally important 11th Principle. Though many people in the community greet by hugging, we now encourage asking “Can I give you a hug?” before greeting someone. Of course, the consent education goes way beyond this to what we describe as “the enthusiastic yes”. I realized how this kind of education, could change the way we interact daily, and I have tried to introduce this to my daily life in the “default world”.

I hope one day soon,

we begin to teach men and women that it is OK to express their fullness. To share

in the pain, and join in opposition without distinctions. To both acknowledge

our intersectionality, and learn to put them aside for the common good. Until

then, I just hope that we learn to have conversations about how to get there by

using language of unity instead of division.

#metoo, #HowIWillChange,

#ihave, #IDidThat, #toughguise, #burningman, #woke, #mentoo

No comments:

Post a Comment